What is the Binomial Theorem?

After you watch the video and know the material, click HERE for the quiz.

While the F.O.I.L. method can be used to multiply any number of binomials together, doing more than three can quickly become a huge headache. Luckily, we've got the Binomial Theorem and Pascal's Triangle for that! Learn all about it in this lesson.

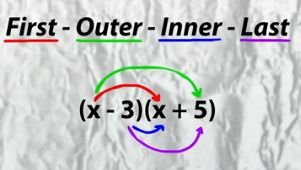

Understanding the F.O.I.L Technique

When I tell people that I'm a high school math teacher, they often share with me what bits of their algebra class they remember. Along with the quadratic formula, the topic I hear the most about is F.O.I.L. It's an acronym that stands for First, Outer, Inner, Last and allows us to multiply two expressions like (x-3)(x+5) by multiplying the first two terms, the outer terms, the inner terms and, finally, the last terms. After we've gotten those things, we simply combine the like terms left in our expression to get our answer,x^2 + 2x - 15.

What F.O.I.L. helps us do is multiply two binomials together to get a trinomial. We begin with binomials because each expression has only two terms, and our answer is a trinomial because it has three terms. Just like a bicycle has two wheels and a tricycle has three!

|

F.O.I.L. Example #1

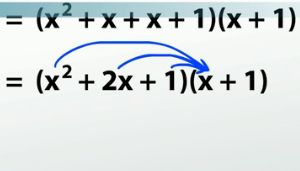

What most people forget is that F.O.I.L. can also help us multiply expressions such as (x + 1)^3. You must first make sure not to make the common mistake of distributing the exponent to both terms on the inside, and instead re-write the expression as (x + 1)(x + 1)(x + 1). We can now begin the process of multiplying these by using F.O.I.L. to multiply the first two binomials as we normally would. We do the firsts, the outers, the inners, the lasts. We combine like terms, and we get x^2 + 2x + 1.

But, we still have another x + 1 hanging out on the end. Now it's time for what I often call the super F.O.I.L. We still need to multiply everything in the first set of parenthesis with everything in the second, but now that now requires more steps. We'll first multiply everything in the trinomial with x((x^2 * x), (2x * 1)) and (1 * x)). We'll then multiply everything in the trinomial with 1 ((x^2 * 1), (2x * 1) and (1 * 1)). Again, we have to combine like terms, and we find that (x + 1)^3 = x^3 + 3x^2 + 3x + 1.

|

This process can be continued for as long as you would like. For example, if we instead wanted to find (x + 1)^4, we could simply multiply our previous answer by x + 1 another time. This now becomes what you might call the super duper F.O.I.L. and requires even more steps. But it's still the same process. If we multiply everything from the first expression (the x + 1) with everything from the second expression (our answer from the last question) and then we combine all our like terms, we'll end up with (x + 1)^4 = x^4 + 4x^3 + 6x^2 + 4x+1.

The Binomial Theorem

But as is now becoming clear, this method requires quite a bit of work. Each time we do it this way there are more and more steps for us to do, and also more opportunities for us to make a silly mistake. Because of this, just the thought of using this method for multiplying, I don't know, (x + 1)^8 gives me a headache. Luckily, we have the Binomial Theorem to save us all the money we would have had to spend Advil.

The binomial theorem is all about patterns. Maybe you noticed that each answer we got began with an x to the same power as in our original problem. (x + 1)^3 began with an x^3. After that, the exponent on the xs went down by 1 until we got to no more xs and simply the number 1. That pattern alone tells us that (x + 1)^8 will look something like x^8 + x^7 + … down to 1. The only things we're missing are the coefficients in front of all those xs. This pattern is definitely more complicated to see, but that's exactly why French mathematician Blaise Pascal got his named attached to it when he found it ( Pascal's Triangle).

Pascal's Triangle

We'll begin by making a triangle that starts with one entry at the top and then gets one entry bigger each row down. Next, we'll fill in the outsides with 1s, giving us this. We now fill in all the remaining entries by adding the two directly above it. Our uppermost blank entry becomes a 2 because 1 + 1 = 2. The next two blank entries become 3 because in the first one 1 + 2 = 3 and in the second one 2 + 1 is also 3. In our next row, (on the left) I get 1 + 3 = 4, then 3 + 3 = 6 and 3 + 1 = 4. Check it out: the rows in Pascal's Triangle are the coefficients from the answers we just got. (x + 1)^4 was 1x^4 + 4x^3 + 6x^2 + 4x + 1. (x + 1)^3 was 1x^3 + 3x^2 + 3x + 1. Which means that if we would do (x + 1)^2, we would get 1x^2 + 2x + 1, if we would just do (x + 1)^1, we would get just 1x + 1, and if we would do (x + 1)^0 - anything to the zero just gives us 1. Notice that this makes the top row the zero row, which means if you're trying to find the coefficients for (x + 1)^2, you actually have to go to the third row down.

So, answering our headache inducing question (x + 1)^8, is as easy as continuing this triangle down to the eighth row. Quickly doing so here tells us that our answer would be the following: 1x^8 + 8x^7 + 28x^6 + 56x^5 + 70x^4 + 56x^3 + 28x^2 + 8x + 1.

Evaluating a More Complex Equation

|

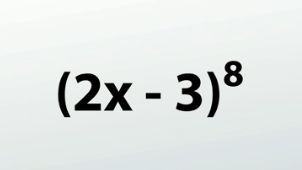

Now, that's all well and good but taking multiples of x + 1 is what you might call a cop out. The binomial theorem gets a little more complex when we, instead, do something like (2x - 3)^8. We can use our previous answer as a framework for solving this one, but wherever I see an x in our answer from the last one, I now have to put a 2x. So, next to the 1 is a 2x ^8, and next to the 8 is a 2x^7, but, just like before, they'll slowly go down. That's not too bad, but the -3 is also going to mess things up pretty good.

Because we had a nice +1 in our last example, we didn't have to worry about this piece of the puzzle. But not only are the xs going to begin with a power of 8 and slowly decrease (go down by 1), the -3 in the example is going to the opposite. Beginning with zero of them, one more -3 will be included in each term from now until the end. So, there's zero -3 in the first, then there's one -3 after the 8, then there's two -3s in the 28 group, then there's three -3s in the 56 group, and they keep on going up and up until there is all eight -3s in the very end by the 1.

If we've plugged all the pieces of this expression into the right spots, it now simply becomes a matter of evaluating powers first. For example, doing 2xˆ8 and getting 256xˆ8. Or possibly, further down the line doing -3ˆ3 and getting -27. After that we have to multiply the numbers in each group, and we end up with this monster of an answer. Notice that the terms alternate between positive and negative numbers. This is because the -3 turns positive when being raised to an even power but remains negative when being raised to an odd power.

It is true that using the binomial theorem for a problem like this may not feel like a short cut or the easy way, but it is definitely still the case that using our F.O.I.L. technique for this question would have been much longer and much more frustrating.

|

Lesson Summary

To Review:

- Binomials are algebraic expressions with two terms

- The Binomial Theorem gives us a method for expanding a binomial that is being raised to an exponent.

- Using the theorem for an expansion has three parts:

- The corresponding row from Pascal's Triangle

- Decreasing powers of the first term

- Increasing powers of the second term

- Finally, multiplying each group of numbers together tells us that (2x-3)^8 is equal to this monster of an expression.